The Left Hand of Darkness, and SciFi

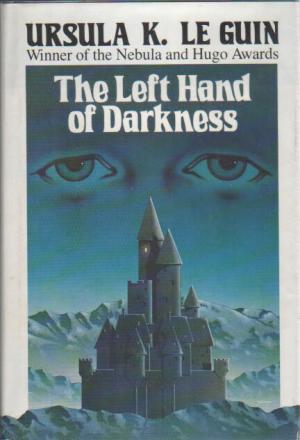

The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula Le Guin, is a Science Fiction (SciFi) book originally published in 1969. At the time, Le Guin was one of the authors who helped revitalize the genre from outdated to the behemoth it is today. Now, the Penguin Group is republishing it in a collector’s edition, alongside five other remarkabale classics of the same era and genre: The Once and Future King, by T. H. White; Stranger in a Strange Land, by Robert A. Heinlein; Dune, by Frank Herbert; 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Arthur C. Clarke; and Neuromancer, by William Gibson — Penguin, apparently, used to have the highest rated SciFi on the market, but has since then diverged into other areas.

The main theme of the The Left Hand of Darkness is not only an other-worldly culture but, more importantly, the ambisexual "humans" that populate it. Genly Ai, the protagonist, is an envoy of a far away alliance of planets tasked with the challenge of convincing the people of the planet Gethen to join its eighty-something other worlds in a somewhat utopian cultural, technological and mystical experience throughout the cosmos. The difficulty of Ai’s mission mostly comes from the consequences of the locals’ lack of sexual differentiation: social rituals and manners are always catching him off-guard, and a method for achieving and maintaining social prestige, shifgrethor, seems to be excessively counter-intuitive for him. On top of all that, he has to deal with the delicate ego balance of a mentally unstable king and a rival country ruled by a fearful bureaucracy.

The ideas which propelled the novel in the 1969 were what piqued my interest, but also what disappointed me the most in reading the book. Le Guin created a plethora of social behaviors and environments as consequences of a unigendered society, but none of them seem to have a strong logical reasoning, they feel like random thoughts on what such a world would be like. The biggest example of this absence of justifications is probably one of the core concepts of the book: shifgrethor social transactions are all based on it, but not even once is there a clear-cut image of what it is; Ai seems to always point out situations when the natives would act in a certain manner while intending a completely different message, leaving us totally in the dark as to what this shifgrethor practice means. Obviously, Le Guin, in an anthropological style, tried to show us an authentic portrait of what a discoverer would encounter; however, it fails to convince, it feels like a poorly performed magic trick.

Fire and fear, good servants, bad lords. (Therem Harth rem ir Estraven, page 187.)

We go along the book reading countless times about the protagonist’s awe and puzzlement with respect to how much different a genderless society is — e.g., "one is respected and judged only as a human being. It is an appalling experience" —, but seldom is there a big enough digression with interesting thoughts on how this difference came to be, only very superficial, basic, conclusions, completely incompatible with what we would expect from an envoy of a galactic alliance. The main character — and the reader — will never fully manage to well understand the local cultures nor its origins; and that, coupled with the lacking of a structural and comprehensive description or exploration of this societal variation leaves a feeling of incompleteness, of a book that did not quite manage to fulfill its promise — in the 1960s, perhaps this miscellanea would be enough for an audience with very little experience on gender ideas, but nowadays it is definitely insufficient. It is quite clear to me that this book needed more pages; in fact, if I didn’t know it was a book, I would say it was a chapter or part of another much bigger work.

A profound love between two people involves, after all, the power and chance of doing profound hurt. (Genly Ai, page 210.)

My critique has not yet made justice to the saga’s strength though, and I must say that at least some of it is very much worth reading and learning from. By far, the best — and worthwhile — part of the whole story is around the last 70 pages, where the main character and his companion — who takes turns in narrating the story — attempt an escape in a fiercely desolate landscape, an environment that strains their physical and emotional energies to the utmost limits, while offering beautiful descriptions and engaging comparisons between normal and ambisexual humans. The dry and straight to the point narration style that is prevalent throughout the book seems to best fit the story at this point and you can finally achieve an emotional connection with the characters.

It’s queer that daylight’s not enough. We need the shadows in order to walk. (Genly Ai, page 224.)

The preface of the series is written by Neil Gaiman, a SciFi veteran author and someone who has quite some interesting thoughts which might explain my harsh criticism of The Left Hand of Darkness. The single most important of his teachings is about the subject of SciFi: it is not the future, but the present. SciFi is only an extrapolation of the present times’ expectations, hopes and dreams for the future; a 1950s future will tell much more about the 1950’s society than the actual future. And, in that regard, perhaps, we should be more indulgent when, 50 years later, we read about the past’s state-of-art simplistic ideas about gender.

I’ve also posted this review on GoodReads, I ended up giving it 4 stars, but, in truth, I would actually give it 3.5 if it were possible to do so.